|

| Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo |

|

n June 27, 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, a Portuguese navigator commissioned by the governor of New Spain to discover a Northwest passage to the orient, set out from Mexico, navigating north along an unfamiliar coastline. His first discovery was San Diego, which he named San Miguel (after Michael the Archangel). Further north, he sailed into Los Angeles harbor, which he named Bahia de los Humos (or “Bay of Smoke,” after the smoke bellowing from many fires made by the local Indian population). Sighting Santa Catalina Island, he named it San Salvador (after his flagship). He christened countless other places he discovered along the coast, but nearly all the names he gave them were changed by later explorers.

|

|

He got as far north as present-day Sonoma County, but missed entirely the bays of Monterey and San Francisco, perhaps due to a storm in the first case and the fog in the latter. According to some accounts, during his return voyage south, Cabrillo not only discovered Monterey Bay, but named it Bahia de los Piños (Bay of the Pines), together with its southern point, Cabo de Piños (Cape of Pines).

Before returning to Mexico, Cabrillo died from an infection resulting from a broken arm he suffered on San Miguel, an island off the coast of Santa Barbara. Sixty years would elapse before another explorer sailing under the Spanish flag would venture along the coast of California.

|

|

| Sebastian Vizcaíno |

|

On May 5, 1602, the Spanish explorer Sebastian Vizcaíno, charged with finding a good harbor in Northern California, set out from Acapulco with four vessels—described as two ships, the San Diego and the Santo Tomás, the frigate Tres Reyes, and a long boat—and, like Cabrillo before him, headed north along the California coastline. Along the way, he permanently named, or renamed, many of the places previously discovered by Cabrillo, including San Diego (after the name of his flagship and the feast of San Diego de Alcalá), and Point Conception (after the vigil of the Immaculate Conception).

On December 16, he rounded a large peninsula and entered a bay that he named for the viceroy of New Spain, Don Gaspár de Zúñiga y Acevedo, Conde de Monte Rey, who had dispatched the expedition. The southern point of the bay, at the thickly-wooded northern tip of the Monterey Peninsula where the pines grew to the water’s edge, he named, Punta de los Piños (Point of the Pines).

On January 3, 1603, after setting up camp near our now-familiar Fisherman’s Wharf in the Monterey Harbor, Vizcaíno set out on a short expedition and discovered the Carmel River and Carmel Bay, named after the Carmelite priests who accompanied him. Though he found a deserted Indian village about a mile from what was to be the site of the Carmel Mission, he encountered no people during his Peninsula reconnoiters. Though archeological evidence suggests that an Indian tribe called the [Ohlones] once inhabited parts of the Monterey Peninsular, the area was apparently uninhabited at the time of Vizcaíno’s arrival.

|

|

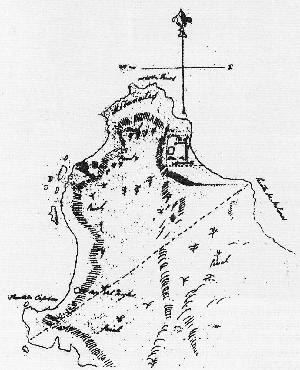

| Early Map of Rancho Punta de Pinos |

|

The Punta de los Piños later became part of a large parcel of 2,667 acres, known as Rancho Punta de los Pinos.

“Ranchos” were large tracts of land granted by the Spanish, and later Mexican, government to private citizens for commercial use, such as cattle raising and farming. The government also set aside “mission” properties, including a church, its gardens and associated buildings and acreage, which were granted to priests to be held in trust for the benefit of the local Indian population, and “pueblo” lands, which were allocated to local governmental authorities to be held in trust for the benefit of the local community.

About 20 private “rancho” land grants were made during the Spanish regime and about 500 during Mexican rule. Under Mexican law, private grants of rancho property were limited to 11 square leagues—about 50,000 acres, or 76 square miles. Each pueblo, or city, was entitled to four leagues of land.

When the United States took possession of California in 1848, it was bound by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to honor the legitimate land claims of Mexican citizens residing there. The Land Act of 1851 established the U.S. Land Commission to review and settle these claims. Of the 813 claims made, the Land Commission approved 553.

The settlement of land titles was often chaotic. The Mexican authorities failed to keep adequate records of the grants and often failed to provide grantees with written evidence of their titles. In addition, many grants, before they could take legal effect, required a series of approvals, such as by the territorial assembly. The land also had to be occupied by the grantee. Very seldom, however, had all of the requirements been fulfilled.

The Rancho Punta de los Piños covered a large slice of the Monterey Peninsula, the perimeter of which extended from Point Cabrillo (formerly, Point Aulones, the current location of the Hopkins Marine Station), following the Pacific Ocean west and then south to Point Cypress, and then back in a straight line to Point Cabrillo. The rancho was originally granted by the Mexican government to Jose Maria Armenta in 1833, and approved on May 17, 1884. But for reasons unknown, the land reverted to the Mexican government and the rancho was re-granted on October 4, 1844 to Jose Abrego, a Monterey hatter, by a deed dated October 4, 1844. The deed was signed by Manuel Michiltorena, the acting governor of the region, and Manuel Jimeno, secretary. In December 1834, Abrego opened a shop in what is now called the Pacheco House. He later became treasurer of Alta California, a position he held until July 7, 1846.

The rancho adjacent to Rancho Punta de los Piños, running along much of the latter’s eastern border, was known as El Pescadero (the “fisherman”). Rancho El Pescadero was one square league (or 4,426 acres), comprising all of the Del Monte forest east of Rancho Punta de los Piños, including Cypress Point, the southern coast of the Monterey Peninsula, and Pebble Beach. Rancho El Pescadero was granted to Fabian Barretto, a Mexican resident of Monterey, in March, 1836, and approved on May 22, 1840.

Within thirty years, however, both Rancho Punta de los Piños and Rancho El Pescadero wound up in the hands of a savy Scotsman who would forever alter the face of Point Piños, the one man perhaps most responsible for the area we now know as Pacific Grove.

|

|